OCIO Conflicts of Interest: Fee Fiddles and Performance Puffery

The chief responsibility of an OCIO is to act as a trusted advisor and a co-fiduciary. Alignment, trust, transparency, and a spirit of partnership are critical ingredients of a successful OCIO relationship. It is therefore essential that institutional investors carefully consider the degree of alignment and potential conflicts of interest of candidate OCIOs.

Regrettably, the alignment of many OCIOs with their prospective clients is compromised by inherent conflicts of interest. Worse still, some OCIOs engage in troubling sleights of hand to win business. Conflicts of interest and sleight of hand tricks are incompatible with the alignment, trust, and spirit of partnership essential to the co-fiduciary role an OCIO should play. These issues can lead to misleading representations of two key factors scrutinized by investors when selecting an OCIO: performance, and fees.

FEE FIDDLES

Fee-related tricks fall into two main areas: the fees charged by the OCIO provider, and the estimates of fees charged by the underlying managers to be included in the portfolio. In both these areas, some OCIO providers obscure the full costs that the asset owner will ultimately incur. These hidden costs include direct costs in the form of higher than expected fees and opportunity costs in the form of subpar performance.

Hidden Fees and Costs - Symptoms of Conflicts of Interest

Some OCIO providers do not fully disclose all of their sources of remuneration. OCIO providers with unrevealed sources of revenue are able to quote what appear to be very low direct fees. These unrevealed revenue sources take a variety of forms, all of which entail conflicts of interest. In our view, this practice should automatically disqualify the candidate OCIO for the simple reason that conflicts of interest are incompatible with serving as a co-fiduciary partner, the essential function of an OCIO.

The Pay to Play

Some OCIO firms receive payments from the underlying managers with whom they invest client assets. Such payments include fees for database inclusion, charges to participate in client conferences, and explicit deals to split manager fees. These arrangements pose a clear conflict of interest, undermining objective manager selection with the business reality of having one eye on the additional revenue that a manager will bring. These arrangements make it impossible to have a clear picture of the sources of revenue and motivations of each agent and these direct and opportunity costs can far exceed any illusory cost savings. Asset owners should instead seek an OCIO whose interests are aligned with their own and who will select managers solely based on the risk-adjusted returns they expect the manager to generate.

The Loss Leader

In a variant of this pay-to-play approach, some firms in effect hire themselves to manage client assets in proprietary products. From this perspective, the OCIO business is a sideline that provides a way to funnel assets to proprietary products. When this is the case, the firm generates the bulk of its earnings from its proprietary products, which subsidize low fees on its OCIO business. Such firms have the incentive to maximize the use of proprietary products across all asset classes, even when there are better options available. The cost to the client is twofold: first, the proprietary products can be costly and may have liquidity and other terms that are disadvantageous. Second, the opportunity cost of proprietary products in the form of foregone investment performance can be high if the proprietary funds do not perform as well as external funds. This opportunity cost, compounded over time, will almost certainly dwarf the apparent fee savings. Just like the OCIOs receiving revenues from external managers, these conflicted OCIOs will be reluctant to liquidate an underperforming internal product for fear of reducing total firm revenue. In contrast, an OCIO implementing an open-architecture approach will not hesitate to take appropriate measures when a manager is not performing as expected.

The Net Trick

A related issue takes advantage of the difficulty of measuring the true costs of the proprietary products. This problem can be particularly acute for fund vehicles that carry two layers of fees—one for the OCIO and one for the underlying (and sometimes proprietary) managers. Because both layers of fees are often deducted directly from the fund’s net asset value, unravelling the total embedded fees can be extremely difficult for a client. We regularly see OCIOs count these vehicles as having zero fees because the fees have been buried in their return streams.

The Cross-Sell, and the Up-Sell

Some firms do not see investment management as their sole business, or even their prime focus. For these firms, providing OCIO services represents a sideline recently added to their main business. Actuarial and consulting firms (many large OCIOs are both actuaries and consultants) fall into this category. Actuarial firms engage in a cross-sell of OCIO services, while, for consultants, OCIO services are an up-sell that in some cases is virtually indistinguishable from their standard consultancy practice. The client is likely to incur a large opportunity cost in the form of foregone investment performance from a firm that does not see OCIO as a competitive advantage, area of particular expertise, and/or main business line. Recent academic research [1] confirms our experience that on average there is no evidence of skill among the firms that have extended their brands into the OCIO realm, despite their claims of stellar performance.

The Broker in OCIO Clothing

Some OCIOs own a brokerage business and channel their clients’ trades to it. This is yet another manifestation of a conflict of interest and poses similar problems to those arising from proprietary products. In this case, the OCIO provider is able to supplement artificially low OCIO fees with the commissions of the brokerage business it owns. The client is likely to suffer from higher brokerage fees and subpar trade execution and will have once again entrusted its assets to a conflicted OCIO in the pursuit of fee savings.

The Package Deal

Some OCIOs do not provide separate quotations of their fees from those of underlying managers, offering only a bundled fee. Because the OCIO keeps all fees not paid to underlying managers, the OCIO is incentivised to include a large proportion of passive strategies, index vehicles, or second-tier managers with low fees, and low-cost asset classes. This mix is unlikely to generate exceptionally strong returns, and the client is left once again to bear the opportunity cost of subpar investment performance compounded over time. In such cases the apparently low bundled fees present a false economy.

The Bait and Switch

Another issue that we have observed involves quoting underlying manager fee estimates based on low-cost vehicles, including, as in the previous case of bundled fees, passive strategies and indexed funds. In this case, the actual investment portfolio ultimately used comprises more expensive active managers and strategies. In this way, the OCIO is able to win business based on lower fees. While the OCIO avoids at least some of the underperformance that would have resulted from retaining the original line up, the asset owner ends up selecting the OCIO for the wrong reasons and will incur higher direct costs.

The best way for an asset owner to understand these conflicts is to ask the right questions and seek transparency with respect to both the various fees received by an OCIO and the types of investments the OCIO intends to employ. To aid this process, we have built a template that an asset owner can use in conducting an OCIO search. The asset owner can require all bidding OCIOs to complete the template which can be downloaded by clicking here and attest to its accuracy. The instructions are contained on sheet 2 of the template. The completed template will allow the asset owner to better understand how each bidding OCIO intends to implement its proposal and the fees and instruments associated with it.

PERFORMANCE PUFFERY

Achieving sustained, risk-adjusted, value-added net of all fees is the ultimate objective of all investors. Sustained strong investment performance achieved at an appropriate level of risk builds wealth over time. Performance is rightly a prime focus of institutions assessing candidate OCIO providers. However, this is another area where conflicts of interest regrettably proliferate.

We believe that OCIO providers should adhere to the highest industry standard when presenting performance history. The record of performance claimed by the OCIO should be based on representative composites constructed using objective criteria comprising the actual experience of a broad set of its clients. We believe that the CFA Institute’s Global Investment Performance Standards (GIPS[2]) provide a widely accepted industry standard with which all OCIO providers should comply.

Below are a few of the tricks employed to boost performance that we most frequently observe.

The Hypothetical Allocation History

Many OCIO firms manage asset class pools that they use as building blocks to offer customized asset allocations to their clients. In some cases, the firm claims GIPS compliance by creating composites at

the asset class level. Some OCIO providers assume allocations to the best performing pools of each period, and present performance of a total portfolio whose asset allocation changes frequently to favor the best performing asset class in each period. They then claim that this hypothetical portfolio is representative of their results, even if no client actually held the portfolio. This approach allows the OCIO provider to claim GIPS compliance while significantly inflating its claimed performance, in some cases by 150-200 basis points over a five-year period. This is an unfortunate perversion of the spirit of GIPS compliance and points to the need to probe deeply into the construction of the performance record in all cases. There should be no prizes for ex-post prescience.

The Backtest Boost

A related gambit is the use of a back tested model to generate a history of holdings across asset classes and sometimes even manager allocations. In our three decades of experience, we have yet to see a back tested model that did not outperform, but we frequently see models that underperform in live implementation. We have even seen back tested allocations to manager products that were themselves only back tests—a double dip of hindsight.

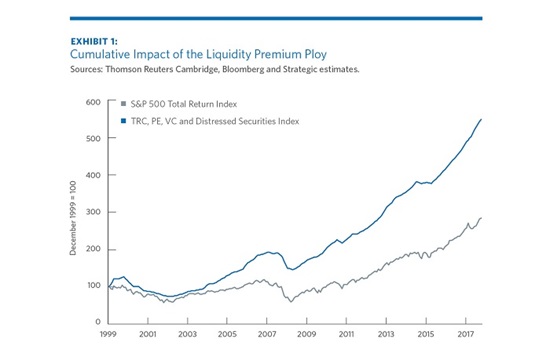

The Liquidity Premium Ploy

Some OCIO providers compare their private equity returns to a publicly traded equity benchmark, such as the S&P 500. This approach compares the returns of an illiquid asset that should command a significant liquidity premium against a benchmark for a very liquid, publicly traded asset that commands no such premium. Considering that the typical liquidity premium sought in private equity is several hundred basis points, this practice sets a very low bar against which to judge private equity performance. Simply adding another source of risk to the portfolio should not count as added value. As illustrated in Exhibit 1, an industry standard private equity benchmark has handily outperformed the S&P 500, generating a large cumulative impact over time.

EXHIBIT 1:

Cumulative Impact of the Liquidity Premium Ploy

The Risk Ruse

A similar problem that we often see is the use of total return histories with no consideration of the risks undertaken to generate the returns. As benchmarking can pose inherent complexities for portfolios that diversify globally and include alternative asset classes, some OCIOs advocate the shortcut of simply comparing total return histories, with no reference to the portfolio’s allocation and volatility. The problem with this approach is that in most environments higher returns are generally associated with higher risk. A related issue arises from the way private equity performance is measured. Because private investments are marked to market infrequently and using a smoothed appraisal process, reported volatility numbers can mask the true economic risk embedded in a performance record. Just as introducing illiquid assets to the portfolio should not count as added value, simply holding a portfolio that on average is more aggressive is not evidence of skill. Again, the best measure of skill takes into account the actual level of risk of and outperformance of a portfolio versus a properly specified benchmark, net of all fees.

The Cherry Pick

Many diversified asset management firms have hundreds of balanced accounts over which they have some level of discretion that could plausibly be relabelled as OCIO mandates. Many consultants are in a similar position, particularly those with a decentralized structure with no “house view.” With potentially hundreds of portfolios to cite as an OCIO track record, and excluding the accounts that have been closed due to weak performance, normal statistical dispersion implies that some of the surviving accounts will have surely performed well. The potential to cherry pick the best performers is an issue of which asset owners must be mindful.

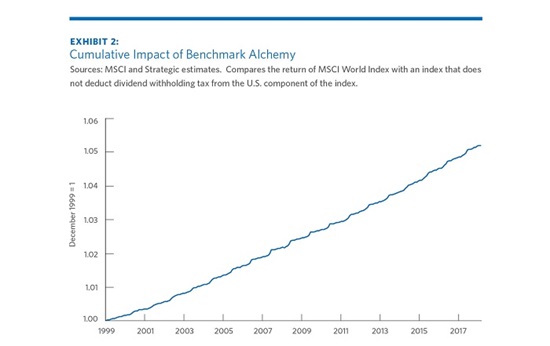

The Benchmark Alchemy

There are widely recognized benchmarks for some asset classes that are considered industry standards because of their representativeness, investability, and transparency. Benchmark construction is complex, however, and some OCIO providers could gravitate to low bar benchmarks in an attempt to burnish their performance record. To take one example, the MSCI World Index is a widely recognized industry benchmark for global equities and has many of the hallmarks of a fair and representative index. Because most investors are subject to withholding taxes on foreign dividends, MSCI publishes a version of the index that subtracts this tax drag from dividend payments globally—the MSCI World Net Total Return Index. U.S. institutional investors, however, are not typically subject to dividend withholding taxes on their U.S. investments, which constitute about 60% of the MSCI World Index. It’s possible to exploit the lower returns of “net” benchmarks like this, even though an OCIO client in the United States is not paying all of the taxes assumed by the benchmark. The impact is significant: using this benchmark for the total equity portfolio of U.S. clients creates ersatz value added of approximately 40 basis points per year with essentially no volatility, puffing up the OCIO provider’s performance record with compounding over time (Exhibit 2). If an OCIO can outperform the benchmark by this much by simply investing in a passive index fund, the deck has been stacked against the client.

EXHIBIT 2:

Cumulative Impact of Benchmark Alchemy

The OCIO search process can be long and intensive, and we hope that we have provided food for thought to assist in the process.

**********

David J. Ordoobadi, CFA, is Managing Director and Economic Counsellor at Strategic Investment Group

Nikki Kraus, CFA, is Managing Director, Global Head of Client Development at Strategic Investment Group

Footnotes

- [1] Cookson, Gordon and Jenkinson, Tim and Jones, Howard and Martinez, Jose Vicente, Investment Consultants’ Claims About Their Own Performance: What Lies Beneath? (July 19, 2018). Available at SSRN: https:// ssrn.com/abstract=3214693

- [2] GIPS® is a registered trademark owned by CFA Institute.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of AlphaWeek or its publisher, The Sortino Group

© The Sortino Group Ltd

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency or other Reprographic Rights Organisation, without the written permission of the publisher. For more information about reprints from AlphaWeek, click here.